Lenin - Introduction

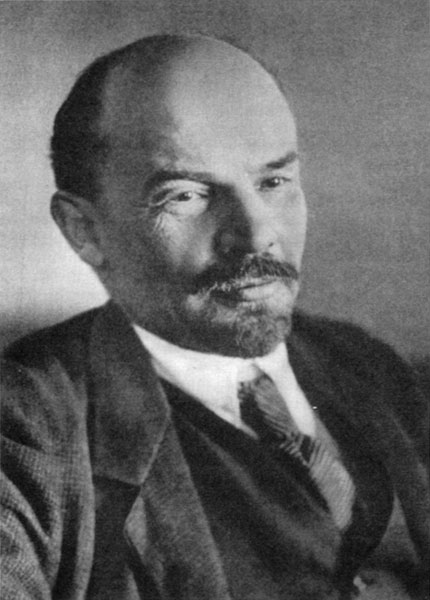

M.S. Nappelbaum's official portrait of Lenin, January 1918. This was the first such photo taken of him after the seizure of power.

Introduction

At the time of the Russian Revolution, the empire ruled by Tsar Nicholas II was vast, stretching over some 22 million square kilometers from the Baltic to the Pacific and from the Arctic to the Black Sea. Over this area, much of which was empty wasteland, was spread a population of 130 million, of whom less than half were "Great Russians", speaking Russian as their mother tongue. The rest of the imperial subjects comprised a turbulent mixture of fiercely nationalistic minorities — Ukranians, Poles, Balts, Kazakhs, Caucasians, Finns, Uzbeks, Armenians, Tartars, Germans, Jews and Mongols. The task of ruling such a vast and variegated population, most of them impoverished peasants engaged in primitive agriculture, was not easy. The country with many nationalities, many languages and a nation largely illiterate, was held together by autocratic means.

It was the overriding preoccupation of keeping the empire together that had marked tsarist rule for the last 300 years. The principal instrument of this policy was a class of dependant landowners who received and retained their estates in return for doing the royal bidding. As "service men" of the tsars, they ruled over the countryside with absolute authority, leading the peasants into battle, levying taxes from them to wage war and punishing those who refused to pay or to fight.

The peasants, who had, over the years, been gradually reduced

from the status of independent farmers to that of serfs, were bound to the land and service of the local squire. Starved, beaten and despised, the Russian serfs were, in fact, close to being slaves. In the eyes of members of the Russian ruling class, the peasantry was a wild beast that had to be feared, chained and kept under guard.

By the 19th century, the more enlightened and intellectual members of the nobility, especially those who had been educated abroad, were increasingly dissatisfied with a system which kept the majority of the Russian people in a state of medieval ignorance and poverty. In 1825, their discontent erupted in an anti-tsarist coup, led by liberal noblemen and army officers. The uprising though quickly suppressed, was the first sign of a conflict between the autocracy and the intelligentsia that was to dominate Russia through the 19th century and into the 20th. The surviving demonstrators, who called themselves Decembrists, were arrested and exiled to Siberia. In the coming years, they came to be seen as heroes among Russian revolutionaries.

Russia entered a catastrophic war with the French, British and Ottomans in the Crimean peninsula, in 1853. The cause for Russia's defeat three years later was not only the incompetence of the military leadership but Russia's primitive economic and social system. Against a rising tide of popular frustration, Tsar Alexander II thought that the best way of averting disaster was to introduce his own reform programme, the principal point of which was the liberation of the serfs. In spite of great opposition from the landowners, Alexander signed the emancipation decree.

Though the rural agrarian peasants were emancipated from serfdom in 1861 its results were far from ideal. The peasants received only half the land that they had been cultivating as serfs, and they had to pay even for that. They were quick to show their displeasure: in the first four months following the emancipation, there were 647 incidents of peasant rioting; and during the year there were 499 major disturbances which had to be put down by the military. In the province of Kazan, 70 rioting villagers were shot dead.

The anger of the peasants was matched by that of the intellectuals, whose demands for legalized political parties and a freely

elected parliament went far beyond anything the Tsar had in mind. Convinced that they would never achieve their objectives through peaceful means, many dissidents turned to terrorism. Their prime target was Tsar Alexander, who escaped six assassination attempts. In March 1881, two members of a terrorist group succeeded in killing the Tsar with a bomb thrown under his coach. The government rushed through a series of draconian new measures which included strict censorship and increased police powers; this further alienated the ordinary, law-abiding citizen without deterring the revolutionaries.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Russian society was further divided, and the Russian tsar estranged from his people as had never been so far. By the early 1900s, the anti-tsarist movement was divided into two main parties — the Socialist Revolutionaries, or SRs, and the Social Democrats. The SRs believed that the only class that was capable of carrying through radical social change was the peasantry who made up 85 percent of the population and lived in an almost permanent state of dissatisfaction. Many SRs believed that the traditional form of village organization, the peasant commune, with its emphasis on common ownership and collective decision-making, was a model for the socialist society of the future.

The Social Democrats found these views "populist" and "utopian" and believed that the struggle for socialism had to be carried out in accordance with "scientific principles" — that is in accordance with the principles laid down by the German left-wing philosopher, Karl Marx. Marx had died in penury after a long exile. His theory purported to explain the prime cause of historical change. In Marx's view, mankind progressed as a result of the conflict that existed between classes, passing through three major stages on the road to political perfection — feudalism, capitalism and socialism. The final stage, socialism would come about when the workers, or proletariat, seized power from their capitalist oppressors and ushered in the first entirely classless — and harmonious — society.

It was the almost religious certainty underlying the theory of history that made Marxism so appealing to the revolutionaries. No matter how hard their struggle or how great their sacrifice, they

found consolation in the belief that time would bring them the ultimate victory.

In Russia, however, where large-scale industrialization had only just begun and the urban proletariat was tiny compared with the peasantry, capitalism was to all appearances only in its infancy, and Marx's necessary conditions for revolution seemed very far away. Meanwhile the Social Democrats had to pursue the vital task of spreading the Marxist message. Soon some agitators began to organize the workers to fight against the government and many felt obliged to disregard the law and constituted authority. Low wages, bad housing and inhumane working conditions had given the proletariat as great a sense of grievance as the peasantry. Urban conditions were dreadful, dangerous and unsanitary. The workers proved highly receptive to the propaganda of the Social Democrats, and some of the party leadership began to look forward to the emergence of a mass labour movement similar to those in more liberal Western countries such as Britain and France. There were others, however, who believed that such a movement would lose its revolutionary character and become a vehicle for reform rather than change. The fiercest critic of the "reformist" view was a young lawyer, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov — better known to his comrades as V. I. Lenin.1

* * *

1. Adapted from The World in Arms, History of the World, Time-Life Series.

The Tsar reformer, Alexander II, with his family

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet