Napoleon - Introduction

Introduction

In spite of all the libels, I have no fear whatever about my fame. Posterity will do me justice. The truth will be known; and the good I have done will be compared with the faults I have committed. I am not uneasy as to the result. Had I succeeded, I would have died with the reputation of the greatest man that ever existed. As it is, although I have failed, I shall be considered as an extraordinary man: my elevation was unparalleled, because unaccompanied by crime. I have fought fifty pitched battles, almost all of which I have won. I have framed and carried into effect a code of laws that will bear my name to the most distant posterity. I raised myself from nothing to be the most powerful monarch in the world. Europe was at my feet. I have always been of opinion that the sovereignty lay in the people. In fact, the imperial government was a kind of republic. Called to the head of it by the voice of the nation, my maxim was, la carrière est ouverte aux talents [the career is opened to talents] without distinction of birth or fortune, and this system of equality is the reason that your oligarchy hates me so much.

Thus napoleon spoke while reflecting upon his amazing career. That was in St Helena where an ungenerous British government had sent the ex-emperor. Napoleon had placed himself under the protection of England in the following words:

(To the Prince Regent of England.) Your Royal Highness:

Exposed to the factions that divide my country and to the enmity of the powers of Europe, I have closed my political career, and I come ... to claim hospitality at the hearth of the British people. I place myself under the protection of their laws, which I demand from Your Royal Highness, as from the most powerful, the most constant, and the most generous of my foes.

But the allied sovereigns and particularly the British had had enough. They did not want to risk a repeat of the Elba island adventure, where Napoleon had been first sent as a ruler of that mini-state, which he then left after only a few months to reclaim his lost empire. This time they wanted to make sure that Napoleon would not rise again.

Napoleon vehemently protested,

August 4th, on board H. M. S. Bellerophon:

I solemnly protest here, in the face of heaven and of men, against the violation of my most sacred rights, in disposing of my person and of my liberty by force. I came on board the Bellerophon freely; I am not the prisoner, I am the guest of England. From the instant I boarded the Bellerophon I was at the hearth of the British people. I appeal to History! It will place on record that an enemy who during twenty years waged war against the British people came freely in his misfortune to seek a refuge under their laws; and what more striking proof could he display of his esteem and of his trust? And how did England reply to such magnanimity? She pretended to hold out the hand of hospitality to her enemy, and when he had placed himself in her power, she slew him!

For the next six years Napoleon was to live in that isolated rocky island in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean, with a very difficult climate, a fact which surely contributed to his early death in 1821. Besides having to live in very rudimentary facilities, Napoleon had to suffer the meanness of the British Governor of St Helena who never missed any occasion to make the life of his

illustrious prisoner more miserable. Napoleon saw that this persecution at the hands of the British would add to his legend:

January 1st, 1817. To bear misfortune was the only thing wanting to my fame. I have worn the imperial crown of France, the iron crown of Italy; England has now given me a greater and more glorious one, - for it is that worn by the Saviour of the world, - the crown of thorns.

Thus it was how this most extraordinary career was to end. When he was exiled, Napoleon was still quite young, not yet fifty. Given his prodigious energy and drive, if he would have been allowed by destiny to remain in power, he could have yet added more accomplishments to the Napoleonian epopee. We have to acknowledge that it is the Revolution that made this epopee possible. Napoleon is a product of the exceptional period of the French revolution. He himself was quite aware that, even with the same extraordinary abilities, he would probably not have the same opportunities that he was able to seize to rise so quickly to exceptional heights. The French army had lost many of its officers who, being from the nobility, had emigrated to escape the rigors of the revolution. Being supremely confident and competent, Napoleon, still in his early twenties, rose to the rank of general, something which could not have happened before the Revolution.

From that moment his truly remarkable talents took him in no time to the top of France and then to the domination of a large part of Europe.

But even this was not necessarily enough for him. Seeing no limits to his possible accomplishments, he even dreamed of a world empire.

Did not you yourself say to me: ‘You let your genius have its way, because it does not know the word impossible.’ How can I help it if a great power drives me on to become dictator of the world? You and the others, who criticise me to-day and would like me to become a good-natured ruler-have not you all been accessories?

I have not yet fulfilled my mission, and I mean to end what I have begun. We need a European legal code, a European court of appeal, a unified coinage, a common system of weights and measures. The same law must run throughout Europe. I shall fuse all the nations into one. ...This, my lord duke, is the only solution that pleases me. ..." (1812: Napoleon to his minister Fouche before the invasion of Russia).

This extreme ambition which saw no limits to what it can accomplish contained in itself the seeds of destruction. The invasion of Russia is a good example. If Napoleon had not embarked in this ill-conceived venture, France would not have lost so much of its Great Army and it is possible that the Empire would have lasted for a much longer time.

But, as Sri Aurobindo, the great sage and yogi, remarked, it is truly difficult to understand such extraordinary personalities. Here is what he wrote about Alexander and Napoleon:

But Alexander of Macedon and Napoleon Buonaparte were poets on a throne, and the part they played in history was not that of incompetents and weaklings. There are times when Nature gifts the poetic temperament with a peculiar grasp of the conditions of action and an irresistible tendency to create their poems not in ink and on paper, but in living characters and on the great canvas of the world; such men become portents and wonders, whom posterity admires or hates but can only imperfectly understand.

This insight from Sri Aurobindo and the expression that he uses to describe Napoleon's fundamental nature, "Poet on a throne", is indeed very illuminating. For it captures in a few words what is supremely important and radical in Napoleon's temperament, the visionary urge.1 This was the basic force driving his superabundant energies. Already during the somewhat ill-fated Egyptian expedition he was dreaming of reaching India both for practical reasons

1. Hence the title of this monograph.

— to get at the British enemy — and for the chance of building some new empire that he was dreaming of. It could not materialize at the time but the preoccupation with India remained with him all along. He also dreamed of united Europe and did try to bring it about repeatedly. One could find of course many reasons why it could not work — historians are still debating on this point — but one which is probably crucial is that, as Sri Aurobindo said, it was difficult to understand him and his grand schemes.

The visionary elan was supported by a superhuman energy: Napoleon was extremely demanding for his close collaborators who struggled to follow the fiery rhythm of his work. During the Consulate, after having spent the day governing, he would come towards the end of the afternoon to the Council of State where he had assembled experts in various fields and work with them through the night on different matters. This was how the famous Code Napoleon — a recasting of all the legal system of France to incorporate the progressive ideas of the Revolution — was elaborated. Often one or the other of the experts would show signs of utter fatigue only to be shaken awake by Napoleon.

"In these sittings," says Roederer, "the First Consul manifested those remarkable powers of attention and precise analysis which enabled him for ten hours at a stretch to devote himself to one object or to several, without ever allowing himself to be distracted by memory or by errant thoughts." ...

Not only are thirty-seven laws discussed at this table; furthermore, the Consul propounds question after question concerning other matters. How is bread made? How shall we make new money? How shall we establish security? He makes all his ministers send detailed reports, and this is great tax upon their energies. But he affects not to notice that they are overworked, and when they get home they often find letters from him requiring an immediate answer. One of his collaborators writes: "Ruling, administering, negotiating with that orderly intelligence of his, he gets through eighteen hours' work every day. In three years he has ruled more than the kings ruled in a century."

He did not like sycophants. After the long hours of work with the Council of State when he was First Consul he would often invite to dinner the person with whom he had argued the most during the frequent debates around their work.

When he noticed that the councilors were simply echoing whatever he said, he was quick to call them to order: "You are not here, gentlemen, to agree with me, but to express your own views. If you do that, I can compare them with mine, and decide which is better."

The energy of Napoleon seemed to have the ability to spread much beyond his physical presence. At the beginning of the Consulate, as First Consul, Napoleon practically became like a dictator; it then looked as if a mass contagion of this new energy happened simultaneously in all the nooks and corners of France:

Within a fortnight after the coup d'etat, he had arranged for the establishment of tax-collecting offices in all the departments, for, as he put it: "Security and property are only to be found in a country which is not subject to yearly changes in the rate of taxation." Two months later, the Bank of France came into being; next year, there were new boards to supervise taxation, the registration of landed property, and forestry. Whereas his predecessors had simply squandered the State domains, he used what was left of them to defray repayment of national debt. ... he continued the process of debt cancellation, renovated the Chambers of Commerce, regulated the Stock Exchange, put an end to speculation in the depreciated currency, stopped the frauds of the army contractors and other war profiteers, and by these and similar measures restored manufacturing industry whose productivity had sunk to a quarter or half of its former level.

What was his magical spell?

At the head of affairs was himself, a man of indomitable energy, and incorruptible. Men of the same stamp, energetic, diligent, and bold, were put in charge of the ministries, the departments and

the prefectures. Favouritism was done away with; sinecures were abolished. Preferment was obtainable only by the efficient, and to them it came regardless of birth or party. All officials, down to the mayors, were appointed from above, and paid from above — "a hierarchy, all First Consuls in miniature," to quote his own words.

On 29th. May 1816, in St Helena, he was remembering so many of these gigantic undertakings, which he called his "treasures" as they were the results of his continuous efforts, whether during rare peace times or even during wars, to upgrade and embellish the infrastructure not only of France but of a large part of Europe:

You want to know the treasures of Napoleon? They are enormous, it is true, but in full view. Here they are: the splendid harbour of Antwerp, that of Flushing, capable of holding the largest fleets; the docks and dykes of Dunkirk, of Le Havre, of Nice; the gigantic harbour of Cherbourg; the harbour works at Venice; the great roads from Antwerp to Amsterdam, from Mainz to Metz, from Bordeaux to Bayonne; the passes of the Simplon, of Mont Cenis, of Mont Genevre, of the Corniche, that give four openings through the Alps; in that alone you might reckon 800 millions. The roads from the Pyrenees to the Alps, from Parma to Spezzia, from Savona to Piedmont; the bridges of Jena, of Austerlitz, of the Arts, of Sevres, of Tours, of Lyons, of Turin, of the Isere, of the Durance, of Bordeaux, of Rouen; the canal from the Rhine to the Rhone, joining the waters of Holland to the Mediterranean; the canal that joins the Scheldt and the Somme, connecting Amsterdam and Paris; that which joins the Ranee and the Vilaine; the canal of Aries, of Pavia, of the Rhine; the draining of the marshes of Bourgoing, of the Cotentin, of Rochefort; the rebuilding of most of the churches pulled down during the Revolution, the building of new ones; the construction of many industrial establishments for putting an end to pauperism; the construction of the Louvre, of the public granaries, of the Bank,

of the canal of the Ourcq; the water system of the city of Paris, the numerous sewers, the quays, the embellishments and monuments of that great city; the public improvements of Rome; the reestablishment of the manufactories of Lyons. Fifty millions spent on repairing and improving the Crown residences; sixty millions' worth of furniture placed in the palaces of France and Holland, at Turin, at Rome; sixty millions worth of Crown diamonds, all of it the money of Napoleon; even the Regent, the only misssing one of the old diamonds of the Crown of France, purchased from Berlin Jews with whom it was pledged for three millions; the Napoleon Museum, valued at more than 400 millions.

These are monuments to confound calumny! History will relate that all this was accomplished in the midst of continuous wars, without raising a loan, and with the public debt actually decreasing day by day.

We have already alluded to the remarkable intellectual capacities of Napoleon, his clarity of mind and precision, his unfailing attention and power of precise analysis, his utter concentration and moreover his exceptional endurance, able as he was to work long hours without faltering when most around him were getting exhausted. He also had the advantage of a prodigious memory:

His unfailing memory was the artillery wherewith he defended the fortress of his brain. Segur, returning from an official inspection of the fortifications on the north coast, sends in a report. "I have read your report," says the First Consul. "It is accurate, but you have forgotten two of the four guns in Ostend. They are on the high road behind the town." Segur is astonished to find that Napoleon is right. His report deals with thousands of guns, scattered all over the place, but the chief pounces on the omission of two.

Supreme intellectual energy but also physical energy: in this time of slow travel with horses, he could cover large distances better than anyone, often working continuously while travelling

and yet hardy rest after arriving, plunging immediately in the business to be attended to. His way of relaxing was to take long baths. He apparently had a slow beating heart - as often have top athletes - and he himself said that the slow circulation of his blood was fortunate as it was counterbalancing the restlessness in his nerves "which otherwise would have made me mad."

Napoleon also had one ability which must have been most useful for a man nearly constantly on the move: he was able to sleep nearly at will. While sitting, if he felt the need, he could take a nap of a few minutes which refreshed him to continue his incessant work. Legend had it that he could even sleep on horseback but it is difficult to see how he would have been able to maintain a rider's posture! But this sleeping capacity must have been precious while travelling as he was so frequently doing in his special carriage:

But he speeds away again, and crosses Germany. Napoleon's carriage is outwardly plain, but within it is comfortably built. The Emperor can sleep in it; by day he can govern from it, just as well as from the Tuileries or from a tent. He is the first to overcome the friction which brings movement to a standstill; and, though he does not travel as fast as we do nowadays, he travels faster than any man ever travelled before. Five days take him from Dresden to Paris. In a number of lock-up drawers within the carriage, he collects reports, dispatches, memoranda; a lantern hanging from the roof lights up the interior; in front of him hangs a list of the different places he must pass through, including where relays of horses are awaiting him. Should a courier reach him, Berthier, or another official who happens to be at hand, must take down the more pressing orders, while the carriage goes jolting on its way. Before long, orderlies are to be seen flying off in every direction.

This exceptional man, very conscious of his personal genius, was also able to be quite simple. He had a special relationship to his troops and soldiers called him affectionately their "petit caporal" (small corporal) as they were aware that he did care for

their well-being even in the rigors of war. He could sit with them in bivouacs, eating the same food as them and discussing with them on various topics. The basic simplicity of his nature manifested even at the supreme moment of his career, during and after the ceremonies of his coronation as Emperor. On that day, he first did a gesture of amazing self-confidence:

Then, when the appointed instant has come, and all are expecting this man who has never bowed the knee to any one, to kneel before the Holy Father, Napoleon, to the amazement of the congregation, seizes the crown, turns his back on the pope and the altar, and standing upright as always, crowns himself in the sight of France. Then he crowns his kneeling wife.

Semblance never holds his attention, which always reaches out to the core of reality. Thus he is not bewildered even in this amazing hour. When he wants to whisper something to his uncle, who stands just in front of him during Mass, he gives the cardinal a gentle dig in the back with his scepter. As soon as all is over, and, alone with Josephine, he goes in to dinner, he says with a sigh of relief: "Thank God we're through with it! A day on the battlefield would have pleased me better!" At their little dinner he tells her to keep on her crown as if he and she were poet and actress, for, he says, she is charming, his little Creole woman as empress. Thus, in the most natural way in the world, he unmasks the whole masquerade, and we are at ease once more as we see the son of the revolution laughing his own empire to scorn.

In fact, despite the unavoidable ruthlessness in a man waging relentless wars in which hundreds of thousand if not millions men perished or were wounded, there was a gentle side of Napoleon. He had a preoccupation with justice and it was one of the reasons which made him reluctant to divorce Josephine for matters of State. He, the strongman feared by so many foes, was strangely weak with his family, often to his own disadvantage:

My force of character has often been praised; yet for my own

family I was nothing but a mollycoddle, and they knew it. The first storm over, their perseverance, their obstinacy, always carried the day; and, from sheer lassitude, they did what they liked with me. I made some great errors there. I did not have the luck Gengis Khan had with his four sons, who knew no emulation save that of serving him well. When I created a king, he at once considered himself by the grace of God. A delusion seized all of them that they were adored, preferred to me. (In St Helena, May 24th 1816)

So was Napoleon, a man uniquely gifted, visionary, epic dreamer, with an iron will yet showing himself at times to be strangely vulnerable like in his relationship to the frivolous and sometimes unfaithful Josephine, whom he passionately loved to the point of being at times quite distracted during some difficult campaigns such as those of Egypt and Italy when he was yet only General Bonaparte. It is also remarkable to see that this man so endowed with a military genius which made him win most of his battles was at the same time acutely aware of the limitations of military force:

"Do you know what amazes me more than any else? The impotence of force to organise anything. There are only two powers in the world: the spirit and the sword. In the long run, the sword will always be conquered by the spirit."

He was quite aware that the supreme power that he had been able to acquire was subject to fatality and nature's whims, as happened when "General Winter" defeated his Great Army in Russia. With all these contradictory aspects of his personality, Napoleon continues to hold a real fascination for the peoples of the world. He is one of the human beings most written about in History. We hope that the few texts we are presenting in this monograph will help the reader to know a little more about this multi-faceted genius.

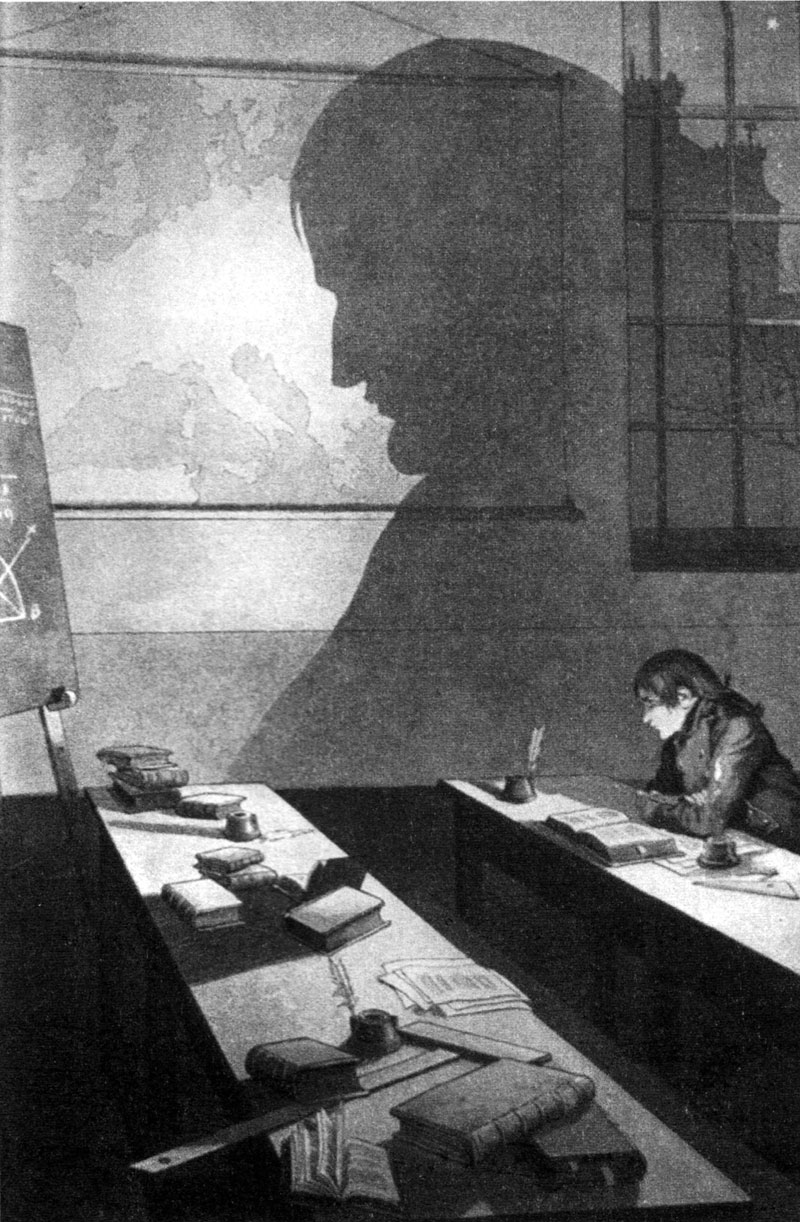

This drawing represents the young Bonaparte on the school benches. His shadow reflects the greatness of the adult and suggests the idea of a unique destiny.

"Napoleon... our last Great Man!"

— Carlyle

The General Bonaparte, by French painter Jacques-Louis David

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet