The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil - Piercing The Veils Of Darkness

Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan

Piercing the Veils of Darkness

The story of Helen Keller's formative years is a wonderful example of the peculiar alchemy wrought by the coming together of perfectly matched teacher and pupil, each fulfilling the other. Anne Mansfield Sullivan was a young, aspiring teacher when she met and started working with the little blind and deaf girl who, under her awakening touch, was transmuted into one of the greatest persons of her time.

Born in 1880 in Tuscumbia, a little town in northern Alabama, USA, Helen Keller was a perfectly normal child until the age of two, when an illness permanently deprived her of sight and hearing. Her subsequent journey from this utterly silent darkness to her position as the world's first well-educated blind and deaf person is a marvellous story.

More than any other, the person who made this possible was Helen's teacher, Anne Sullivan. It is difficult to decide which of the two was more remarkable: Helen Keller, the brilliant and exemplary pupil who overcame seemingly insurmountable odds to achieve learning: or Anne Sullivan, the totally self-giving and self-effacing teacher, who for close to a decade and a half devoted every minute of her time to helping her pupil.

To understand their story, one must first understand the particular difficulty that the blind and deaf face: they have to rely solely on their sense of touch to contact the outside world. In the last century, relatively little was known of how to educate such handicapped persons and Helen Keller's achievements blazed a trail through virgin land.

Anne Sullivan came to Helen in 1887 when the latter was seven years old. She herself had just graduated from the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston, which she had joined after becoming almost totally blind at a very early age. Although her sight was later partially restored, her education in this Institute, which began at the most elementary level, gave her a unique understanding of the handicap of blindness.

She had only a few months to prepare for her work with Helen, and almost no guidance on the method to be used. Her only help was the example of Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe who, just a few years before, had succeeded in teaching language to a blind and deaf child through raised type. This pioneering work was Anne's first guide, but every subsequent step was based on her own intuitive understanding of what was best for the child in her care. She did not keep any record of her work, nor did she follow a particular method, but she learned from her task constantly, keeping the best interests of her pupil in mind. That she gave her self utterly to this task, never leaving the side of her pupil, always available to interpret and to direct, is obvious from her letters to friends and from Helen Keller's account of her education.

To start with, Miss Sullivan made contact with the child's mind through the sense of touch. Slowly Helen learned the manual alphabet by connecting words with objects. In a little while she could read and write in Braille. In a few years the child was transformed. Books became her constant companions. Soon her desire to read encompassed the most serious literature, and books had to be specially embossed for her. She developed a large correspondence and long letters were exchanged with her many friends, some of them the most eminent persons of the day. Poets and writers like John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Mark Twain had but to come in contact with this radiant soul to fall in love with her. Alexander Graham Bell was from the first a guiding light in her life, watching her progress with infinite interest.

Until the age of ten Helen could communicate only with the sign language of the deaf-mute. This condition was most unsatisfactory for her and she resolved to ,learn to speak. That this was considered a near impossibility did not deter her. She was used to measuring herself by the standards of a normal person, protesting vehemently at any attempted easing of her taxing daily schedule. The only means Helen had of distinguishing the thousands of intonations that make up habitual speech was to place her hands on the lips and throat of her teacher and then do the same to herself, and try to imitate the sound. This had to be repeated hundreds of times before a satisfactory result was achieved.

The pain and heartache of this struggle is described in her own words, and the fact that she succeeded is proof of her indomitable spirit. She could not have done

so without her teacher. So close were they that they would seem to be one being in two bodies. Miss Sullivan describes how Helen could often "hear" sounds just by being in physical contact with her teacher, although it was indubitably proved that the child was stone-deaf.

Having learned speech, Helen decided she wished to go to college. Here too her teacher' s aid became indispensable as Helen strove to keep up with the rest of the seeing and hearing students. All the books of which embossed copies did not exist had to be read to her by Miss Sullivan. Besides English, she learned French, German, Latin and Greek. She did all her writing on a typewriter, though once having typed something she had no way to check what she had written unless someone read it out to her.

Helen graduated from Radcliffe with honours in 1904. After this she became concerned with the conditions of the blind and deaf and soon was active on the staff of the American Association for the Blind. The indefatigable energy that she had given to her own education she now spent in improving the lives of handicapped persons all over the world. She travelled extensively, met hundreds of people, charming everyone with the radiance and purity of her soul. Mark Twain said that she and Napoleon were the two most interesting characters of the nineteenth century. Her whole life was a series of attempts to do what other people do as well as they do it. That she succeeded to the fullest is in no small measure because of the unfailing support of her teacher, who was also her dearest friend and the wisest of advisors. It has verily been said that the world would not have heard of Helen Keller if Anne Sullivan had not been there.

Anne Sullivan gave the best years of her life to Helen, seldom leaving her side until her pupil had graduated from college. The principles of teaching that Anne Sullivan evolved through her association with Helen are applicable universally. The fundamental point was to draw out the innate, latent capabilities within the child, taking care not to destroy her originality in the artificial atmosphere of a classroom where lessons are "taught". One of her most strongly held beliefs was never to silence a child who asks questions. She urged everyone to talk to Helen naturally, to give her full sentences and intelligent ideas, never minding whether Helen understood or not. Similarly, she did not believe in imposing tasks and ideas that would be wearisome or distasteful. Every child is naturally curious and she believed in satisfying this curiosity and using it as a door to the child's mind. It was her genius for sensing the right approach for each situation that helped create the phenomenon of Helen Keller. Her approach remains of perennial value to all teachers of young children.

Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan

When Anne Sullivan came to Helen, she found a strong-willed, healthy child, completely spoilt, who was used to getting her own way by throwing the most violent tantrums. Her parents had been utterly at a loss in finding a way to deal with her. Almost the first thing Anne did was to separate Helen from her family and literally battle it out with the willful child until she could establish contact with her. In her own words:

I could do nothing with Helen in the midst of the family, who have always allowed her to do exactly as she pleased. She has tyrannized over everybody, her mother, her father, the servants... and nobody had ever seriously disputed her will... until I came.... As I began to teach her, I was beset by many difficulties. She wouldn't yield a point without contesting it to the bitter end ... I meant to go slowly... I had an idea that I could win the love and confidence of my little pupil by the same means that I should use if she could see and hear. But I soon found that I was cut off from all the usual approaches to the child's heart.... Thus it is, we study, plan and prepare ourselves for a task, and when the hour for action arrives, we find that the system we have followed with such labour and pride does not fit the occasion; and then there's nothing for us to do but rely on something within us, some innate capacity for knowing and doing, which we did not know we possessed until the hour of our great need brought it to light.1

She started to spell words into Helen's hand, and the child, thinking this a new game, learned the movements quickly without understanding the connection between things and their names. And then one day a miracle happened. The incident is described by Helen:

The morning after my teacher came she led me into her room and gave me a doll.... When I had played with it a little while, Miss Sullivan slowly spelled into my hand the word "d-o-1-1." I was at once interested in this finger play and tried to imitate it. When I finally succeeded in making the letters correctly I was flushed with childish pleasure and pride... I did not know that I was spelling a word or even that words existed; I was simply making my fingers go in monkey-like imitation. In the days that followed I learned to spell in this uncomprehending way a great many words.. .2

This went on for several days until one day...

We walked down the path to the well-house... Some one was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first

slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of . something forgotten — a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that could in time be swept away. I left the well-house eager to learn. Everything had a name, and each name gave birth to a new thought. As we returned to the house every object which I touched seemed to quiver with life. That was because I saw everything with the strange, new sight that had come to me.3

I recall many incidents of the summer of 1887 that followed my soul's sudden awakening. I did nothing but explore with my hands and learn the name of every object that I touched; and the more I handled things and learned their names and uses, the more joyous and confident grew my sense of kinship with the rest of the world.4

Here is her teacher's description of the morning after this incident, which transformed the little child.

... Helen got up this morning like a radiant fairy. She has flitted from object to object, asking the name of everything and kissing me for very gladness. Last night when I got in bed, she stole into my arms other own accord and kissed me for the first time, and I thought my heart would burst, so full was it of joy.5

Anne Sullivan groped for a way to start teaching language to the child:

I have decided not to try to have regular lessons for the present. I am going to treat Helen exactly like a two-year-old child. It occurred to me the other day that it is absurd to require a child to come to a certain place at a certain time and recite certain lessons, when he has not yet acquired a working vocabulary.. .. I asked myself, "How does a normal child learn language?" The answer was simple, "By imitation." The child comes into the world with the ability to learn, and he learns of himself, provided he

is supplied with sufficient outward stimulus. He sees people do things, and he tries to do them. He hears others speak, and he tries to speak. But long before he utters his first word, he understands what is said to him... These observations have given me a clue to the method to be followed in teaching Helen language. I shall talk into her hand as we talk into the baby's ears. I shall assume that she has the normal child's capacity of assimilation and imitation. I shall use complete sentences in talking to her, and fill out the meaning with gestures and her descriptive signs when necessity requires it; but I shall not try to keep her mind fixed on any one thing. I shall do all I can to interest and stimulate it, and wait for results.6

Since I have abandoned the idea of regular lessons, I find that Helen learns much faster. I am convinced that the time spent by the teacher in digging out of the child what she has put into him, for the sake of satisfying herself that it has taken root, is so much time thrown away. It's much better, I think, to assume that the child is doing his part, and that the seed you have sown will bear fruit in due time. It's only fair to the child, anyhow...7

From the beginning, Anne Sullivan's "classroom " was life itself— nature, the garden, people — and she "spoke " to Helen of everything.

... I don't want any more kindergarten materials.... I am beginning to suspect all elaborate and special systems of education. They seem to me to be built up on the supposition that every child is a kind of idiot who must be taught to think. Whereas, if the child is left to himself, he will think more and better, if less showily. Let him go and come freely, let him touch real things and combine his impressions for himself, instead of sitting indoors at a little round table, while a sweet-voiced teacher suggests that he build a stone wall with his wooden blocks, or make a rainbow out of strips of coloured paper, or plant straw trees in bead flower-pots. Such teaching fills the mind with artificial associations that must be got rid of, before the child can develop independent ideas out of actual experiences.8

We have begun to take long walks every morning... Indeed, I feel as if I

had never seen anything until now, Helen finds so much to ask about along the way. ... Every new word Helen learns seems to carry with it necessity for many more. Her mind grows through its ceaseless activity.9

Helen describes the way her teacher went about the task of awakening her:

Thus I learned from life itself At the beginning I was only a little mass of possibilities. It was my teacher who unfolded and developed them. When she came, everything about me breathed of love and joy and was full of meaning. She has never since let pass an opportunity to point out the beauty that is in everything, nor has she ceased trying in thought and action and example to make my life sweet and useful.

It was my teacher's genius, her quick sympathy, her loving tact which made the first years of my education so beautiful. It was because she seized the right moment to impart knowledge that made it so pleasant and acceptable to me. She realized that a child's mind is like a shallow brook which ripples and dances merrily over the stony course of its education and reflects here a flower, there a bush, yonder a fleecy cloud; and she 9 attempted to guide my mind on its way, knowing that like a brook it should be fed by mountain streams and hidden springs, until it broadened out into a deep river, capable of reflecting in its placid surface, billowy hills, the liminous shadows of trees and the blue heavens, as well as the sweet face of a little flower.

Any teacher can take a child to the classroom, but not every teacher can make him learn. He will not work joyously unless he feels that liberty is his, whether he is busy or at rest; he must feel the flush of victory and the heart-sinking of disappointment before he takes with a will the tasks distasteful to him and resolves to dance his way bravely through a dull routine of textbooks.

My teacher is so near to me that I scarcely think of myself apart from her. How much of my delight in all beautiful things is innate, and how much is due to her influence, I can never tell. I feel that her being is inseparable A( from my own, and that the footsteps of my life are in hers. All the best of me belongs to her — there is not a talent, or an aspiration or a joy in me that has not been awakened by her loving touch.10

The most important day I remember in all my life is the one on which my teacher, Anne Mansfield Sullivan, came to me. I am filled with wonder when I consider the immeasurable contrasts between the two lives which it connects...11

Have you ever been at sea in a dense fog, when it seemed as if a tangible white darkness shut you in, and the great ship, tense and anxious, groped her way toward the shore with plummet and sounding-line, and you waited with beating heart for something to happen? I was like that ship before my education began, only I was without compass or sounding-line, and had no way of knowing how near the harbour was. "Light! give me light!" was the wordless cry of my soul, and the light of love shone on me in that very hour."12

From the beginning of my education Miss Sullivan made it a practice to speak to me as she would speak to any hearing child; the only difference was that she spelled the sentences into my hand instead of speaking them. If I did not know the words and idioms necessary to express my thoughts she supplied them, even suggesting conversation when I was unable to keep up my end of the dialogue...

The deaf and the blind find it very difficult to acquire the amenities of conversation. How much more this difficulty must be augmented in the case of those who are both deaf and blind! They cannot distinguish the tone of the voice or, without assistance, go up and down the gamut of tones that give significance to words; nor can they watch the expression ¦ of the speaker's face, and a look is often the very soul of what one says.13

Thus within a few months, a child who had had no means of communicating with the world except to scream and kick for what she wanted, was transformed into an eager, ardent pupil, asking endless questions, radiant and joyful in her delight in all things. Everything stimulated her interest and Miss Sullivan took care to answer all her questions, even if she was sometimes severely taxed to find satisfying answers. Hundreds of words and sentences were spelled into Helen s hand all day long so that she was able to absorb much of the life around her which her lack of sight and hearing veiled. In keeping with her resolve not to deny her any of the experiences that would normally come in a child's way, she took Helen to the circus, and the

child touched each animal to discover its shape. She was taken to the beach, where she experienced the might and grandeur of the ocean, demanding an answer to her indignant question: "Who has put salt in the water? " Helen tells us more about her learning process:

For a long time I had no regular lessons. Even when I studied most earnestly it seemed more like play than work. Everything Miss Sullivan taught me she illustrated by a beautiful story or a poem. Whenever anything delighted or interested me she talked it over with me just as if she were a little girl herself. What many children think of with dread, as a painful plodding through grammar, hard sums and harder definitions, is to-day one of my most precious memories.

I cannot explain the peculiar sympathy Miss Sullivan had with my pleasures and desires... Added to this she had a wonderful faculty for description. She went quickly over uninteresting details, and never nagged me with questions to see if I remembered the day-before- yesterday's lesson. She introduced dry technicalities of science little by little, making every subject so real that I could not help remembering what she taught.

We read and studied out of doors, preferring the sunlit woods to the house. All my early lessons have in them the breath of the woods — the fine, resinous odour of pine needles, blended with the perfume of wild grapes. Seated in the gracious shade of a wild tulip tree, I learned to think that everything has a lesson and a suggestion.14

Thus the stimulus was provided for Helen's innate genius to flower. In a year Helen had changed completely. In the words of her teacher, from a report written in1888, Helen's eighth year:

... her whole body is so finely organized that she seems to use it as a medium for bringing herself into closer relations with her fellow creatures. She is able not only to distinguish with great accuracy the different undulations of the air and the vibrations of the floor made by various sounds and motions, and to recognize her friends and acquaintances the instant she touches their hands or clothing, but she also perceives the state of mind of those around her. It is impossible for any

one with whom Helen is conversing to be particularly happy or sad, and withhold the knowledge of this fact from her.15

Having mastered language, Helen was eager to learn to speak normally, which, as far as she knew, a blind-deaf child had never achieved. Then one day Helen heard of a girl in Norway, blind and deaf like herself, who had been taught to speak. She decided to learn to speak whatever it might cost her. Here she describes the struggle she underwent:

The impulse to utter audible sounds had always been strong within me. I used to make noises, keeping one hand on my throat while the other hand felt the movements of my lips...

I had known for a long time that the people about me used a method of communication different from mine; and even before I knew that a deaf child could be taught to speak, I was conscious of dissatisfaction with the means of communication I already possessed. One who is entirely dependent upon the manual alphabet has always a sense of restraint, of narrowness....

No dear child who has earnestly tried to speak the words which he has never heard — to come out of the prison of silence, where no tone of love, no song of bird, no strain of music ever pierces the stillness — can forget the thrill of surprise, the joy of discovery which came over him when he uttered his first word. Only such a one can appreciate the eagerness with which I talked to my toys, to stones, trees, birds and dumb animals, or the delight I felt when at my call Mildred [her sisterran to me or my dogs obeyed my commands. It is an unspeakable boon to me to be able to speak in winged words that need no interpretation. As I talked, happy thoughts fluttered up out of my words that might perhaps have struggled in vain to escape my fingers....

But for Miss Sullivan's genius, untiring perseverance and devotion, I could not have progressed as far as I have toward natural speech. In the first place, I laboured night and day before I could be understood even by my most intimate friends; in the second place, I needed Miss Sullivan's assistance constantly in my efforts to articulate each sound clearly and to combine all sounds in a thousand ways....

In reading my teacher's lips I was wholly dependent on my fingers: I had

to use the sense of touch in catching the vibrations of the throat, the movements of the mouth and the expression of the face; and often this sense was at fault. In such cases I was forced to repeat the words or sentences, sometimes for hours, until I felt the proper ring in my own voice.16

Just as Miss Sullivan supported Helen in her struggle for normal speech, she was there when Helen decided she wished to go to college. After overcoming the greatest difficulties, Helen was accepted at Radcliffe.

I remember my first day at Radcliffe. It was a day full of interest for me. I had looked forward to it for years. A potent force within me, stronger than the persuasionof my friends, stronger even than the pleadings of my heart, had impelled me to try my strength by the standards of those who see and hear. I knew that there were obstacles in the way; but I was eager to overcome them.... Debarred from the great highways of knowledge, I was compelled to make the journey across country by unfrequented roads —that was all,... 17

I am frequently asked how I overcome the peculiar conditions under which I work in college. In the classroom I am of course practically alone. The professor is as remote as if he were speaking through a telephone. The lectures are spelled into my hand as rapidly as possible, and much of the individuality of the lecturer is lost to me in the effort to keep in the race. The words rush through my hand like hounds in pursuit of a hare which they often miss.... Usually I jot down what I can remember of them when I get home....18

Miss Sullivan gave herself utterly to helping her pupil and in the process almost ruined her already delicate eyes. Helen expressed her anguish in a letter to a friend:

... I am now sure that I shall be ready for my examinations in June. There is but one cloud in my sky at present; but that is one which casts a dark shadow over my life, and makes me very anxious at times. My teacher's eyes are no better: indeed, I think they grow more troublesome, though

she is very brave and patient, and will not give up. But it is most distressing to me to feel that she is sacrificing her sight for me. I feel as if I ought to give up the idea of going to college altogether: for not all the knowledge in the world could make me happy, if obtained at such a cost. I do wish ... you would try to persuade Teacher to take a rest, and have her eyes treated. She will not listen to me.19

More than anyone can intimate or estimate, the story of Helen Keller is the story of Anne Mansfield Sullivan. This is not said to minimize the heroic achievements of the one, but to do justice to the intelligent, affectionate, and courageous devotion of the other.

References

|

1. Helen Keller, The Story of My Life (New York: Lancer, 1968), pp. 360-61. |

|

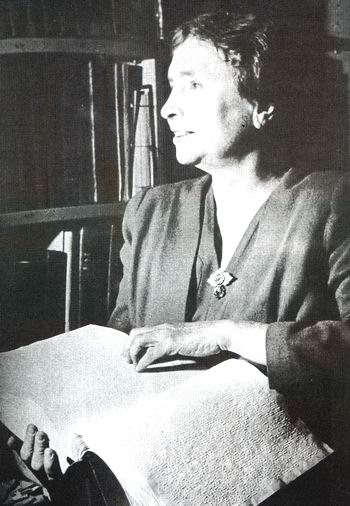

Helen Keller reading Braille, 1950

The following passages are from the paper Anne Sullivan prepared for the July 1894 meeting of the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf.

You must not imagine that as soon as Helen grasped the idea that everything had a name she at once became mistress of the treasury of the English language, or that "her mental faculties emerged, full armed, from their then living tomb, as Pallas Athena from the head of Zeus," as one other enthusiastic admirers would have us believe. At first, the words, phrases and sentences which she used in expressing her thoughts were all reproductions of what we had used in conversation with her, and which her memory had unconsciously retained. And indeed, this is true of the language of all children. Their language is the memory of the language they hear spoken in their homes. Countless repetition of the conversation of daily life has impressed certain words and phrases upon their memories, and when they come to talk themselves, memory supplies the words they lisp. Likewise, the language of educated people is the memory of the language of books.

Language grows out of life, out of its needs and experiences. At first my little pupil's mind was all but vacant. She had been living in a world she could not realize.Language and knowledge are indissolubly connected; they are interdependent. Good work in language presupposes and depends on a real knowledge of things. As soon as Helen grasped the idea that everything had a name, and that by means of the manual alphabet these names could be transmitted from one to another, I proceeded to awaken her further interest in the objects whose names she learned to spell with such evident joy. I never taught language for the PURPOSE of teaching it; but invariably used language as a medium for the communication of thought; thus the learning of language was coincident with the acquisition of knowledge. In order to use language intelligently, one must have something to talk about, and having something to talk about is the result of having had experiences; no amount of language training will enable our little children to use language with ease and fluency unless they have something clearly in their minds which they wish to communicate, or unless we succeed in awakening in them a desire to know what is in the minds of others.

At first I did not attempt to confine my pupil to any system. I always tried to find out what interested her most, and made that the starting-point for the new lesson, whether it had any bearing on the lesson I had planned to teach or not. During the first two years of her intellectual life, I required Helen to write very little. In order to write one must have something to write about, and having something to write about requires some mental preparation. The memory must be stored with ideas and the mind must be enriched with knowledge before writing becomes a natural and pleasurable effort. Too often, I think, children are required to write before they have anything to say. Teach them to think and read and talk without self-repression, and they will write because hey cannot help it.

Helen acquired language by practice and habit rather than by study of rules and definitions. Grammar with its puzzling array of classifications, nomenclatures, and paradigms, was wholly discarded in her education. She learned language by being brought in contact with the living

language itself; she was made to deal with it in everyday conversation, and in her books, and to turn it over in a variety of ways until she was able to use it correctly. No doubt I talked much more with my fingers, and more constantly than I should have done with my mouth; for had she possessed the use of sight and hearing, she would have been less dependent on me for entertainment and instruction.

I believe every child has hidden away somewhere in his being noble capacities which may be quickened and developed if we go about it in the right way; but we shall never properly develop the higher natures of our little ones while we continue to fill their minds with the so-called rudiments. Mathematics will never make them loving, nor will the accurate knowledge of the size and shape of the world help them to appreciate its beauties. Let us lead them during the first years to find their greatest pleasure in Nature. Let them run in the fields, learn about animals, and observe real things. Children will educate themselves under right conditions. They require guidance and sympathy far more than instruction.

I think much of the fluency with which Helen uses language is due to the fact that nearly every impression which she receives comes through the medium of language. But after due allowance has been made for Helen's natural aptitude for acquiring language, and for the advantage resulting from her peculiar environment, I think that we shall still find that the constant companionship of good books has been of supreme importance in her education. It may be true, as some maintain, that & language cannot express to us much beyond what we have lived and experienced; but I have always observed that children manifest the greatest delight in the lofty, poetic language which we are too ready to think beyond their comprehension. "This is all you will understand," said a teacher to a class of little children, closing the book which she had been reading to them. "Oh, please read us the rest, even if we won't understand it," they pleaded, delighted with the rhythm, and the beauty which they felt, even though they could not have explained it. It is not necessary that a child should understand every word in a book before he can read with pleasure and profit. Indeed, only such explanations should be given as are really essential. Helen drank in language which she at first could not understand, and it remained in her mind until needed, when it fitted itself naturally and easily into her conversation and compositions. Indeed, it is maintained by some that she reads too much, that a great deal of originative force is dissipated in the enjoyment of books; that when she might see and say things for herself, she sees them only through the eyes of others, and says them in their language; but I am convinced that original composition without the preparation of much reading is an impossibility. Helen has had the best and purest models in language constantly presented to her, and her conversation and her writing are unconscious reproductions of what she has read. Reading, I think, should be kept independent of the regular school exercises. Children should be encouraged to read for the pure delight of it. The attitude of the child toward his books should be that of unconscious receptivity. The great works of the imagination ought to become a part of his life, as they were once of the very substance of the men who wrote them. It is true, the more sensitive and imaginative the mind is that receives the thought-pictures and images of literature, the more nicely the finest lines are reproduced. Helen has the vitality of feeling, the freshness and eagerness of interest, and the spiritual insight of the artistic temperament, and

language itself; she was made to deal with it in everyday conversation, and in her books, and to turn it over in a variety of ways until she was able to use it correctly. No doubt I talked much more with my fingers, and more constantly than I should have done with my mouth; for had she possessed the use of sight and hearing, she would have been less dependent on me for entertainment and instruction.

I believe every child has hidden away somewhere in his being noble capacities which may be quickened and developed if we go about it in the right way; but we shall never properly develop the higher natures of our little ones while we continue to fill their minds with the so-called rudiments. Mathematics will never make them loving, nor will the accurate knowledge of the size and shape of the world help them to appreciate its beauties. Let us lead them during the first years to find their greatest pleasure in Nature. Let them run in the fields, learn about animals, and observe real things. Children will educate themselves under right conditions. They require guidance and sympathy far more than instruction.

I think much of the fluency with which Helen uses language is due to the fact that nearly every impression which she receives comes through the medium of language. But after due allowance has been made for Helen's natural aptitude for acquiring language, and for the advantage resulting from her peculiar environment, I think that we shall still find that the constant companionship of good books has been of supreme importance in her education. It may be true, as some maintain, that & language cannot express to us much beyond what we have lived and experienced; but I have always observed that children manifest the greatest delight in the lofty, poetic language which we are too ready to think beyond their comprehension. "This is all you will understand," said a teacher to a class of little children, closing the book which she had been reading to them. "Oh, please read us the rest, even if we won't understand it," they pleaded, delighted with the rhythm, and the beauty which they felt, even though they could not have explained it. It is not necessary that a child should understand every word in a book before he can read with pleasure and profit. Indeed, only such explanations should be given as are really essential. Helen drank in language which she at first could not understand, and it remained in her mind until needed, when it fitted itself naturally and easily into her conversation and compositions. Indeed, it is maintained by some that she reads too much, that a great deal of originative force is dissipated in the enjoyment of books; that when she might see and say things for herself, she sees them only through the eyes of others, and says them in their language; but I am convinced that original composition without the preparation of much reading is an impossibility. Helen has had the best and purest models in language constantly presented to her, and her conversation and her writing are unconscious reproductions of what she has read. Reading, I think, should be kept independent of the regular school exercises. Children should be encouraged to read for the pure delight of it. The attitude of the child toward his books should be that of unconscious receptivity. The great works of the imagination ought to become a part of his life, as they were once of the very substance of the men who wrote them. It is true, the more sensitive and imaginative the mind is that receives the thought-pictures and images of literature, the more nicely the finest lines are reproduced. Helen has the vitality of feeling, the freshness and eagerness of interest, and the spiritual insight of the artistic temperament, and

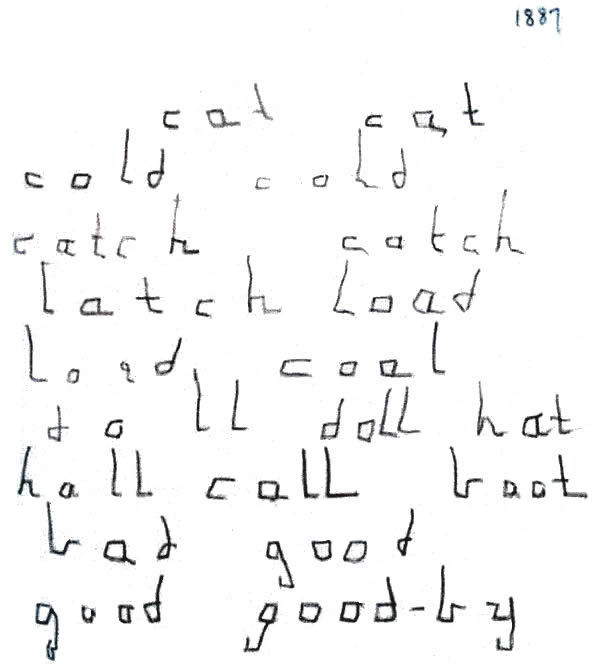

Helen's early writing. This page is dated June 20th 1887. One can read: cold, catch, latch, load,

lord, coal, doll, hat, bad and good-by. Compare with a later piece of writing p. 333.

naturally she has a more active and intense joy in life, simply as life, and in nature, books, and people than less gifted mortals. Her mind is so filled with the beautiful thoughts and ideals of the great poets that nothing seems commonplace to her; for her imagination colours all life with its own rich hues.

From Helen Keller, The Story of My Life (New York: Lancer, 1968), pp. 449-53.

Braille

Braille, the universally accepted system of writing used by and for blind persons, consists of a code of sixty-three characters, each made up of one to six raised dots arranged in a six-position matrix or cell. These Braille characters are embossed in lines on paper and read by passing the fingers lightly over the manuscript. Louis Braille (1809-52), who was blinded at the age of three, invented the system in 1824 while a student at the Institution Nationale des Jeunes Aveugles (National Institute for Blind Children), Paris.

Braille's Invention

When Louis Braille entered the school for the blind in Paris, in 1819, it had fourteen books in embossed characters available for the students, but they were rarely used. In addition to the difficulty encountered by even the best readers using this system, and the slow pace at which they had to proceed, there was another disadvantage of which the young Braille and his classmates were keenly aware: there was no way for them to write using the raised lines of this system. Braille learned of a system of tangible writing using dots, invented in 1819 by Captain Charles Barbier, a French army officer. It was called night writing and was intended for night-time battlefield communications. In 1824, when he was only fifteen years old. Braille developed a six-dot "cell" system. He used Barbier 's system as a starting point and cut its twelve-dot configuration in half. The system was first published in 1829; a more complete elaboration appeared in 1837.

Diffusion of Braille

A Braille's system was immediately accepted and used by his fellow students, but wider acceptance was slow in coming. The system was not officially adopted by the school in Paris until 1854, two years after Braille's death. A universal Braille code for the English-speaking world was not adopted until 1932, when representatives from agencies for the blind in Great Britain and United States met in London and agreed upon a system known as Standard English Braille, grade 2. In 1957 Anglo-American experts again met in London to further improve the system.

In addition to the literary Braille code, there are other codes utilizing the Braille cell but with other meanings assigned to each configuration.

The "Nemeth Code of Braille Mathematics and Scientific Notation" (1965) provides for Braille representation of the many special symbols used in advanced mathematical and technical material. There are also special braille codes or modifications for musical notation, shorthand, and, of course, many of the more common languages of the world.

Handwritten Braille

Writing Braille by hand is accomplished by means of a device called a slate that consists of two

metal plates hinged together to permit a sheet of paper to be inserted between them. Some slates have a wooden base or guide board onto which the paper is clamped. The upper of the two metal plates, the guide plate, has cell-sized windows; under each of these, in the lower plate, are six slight pits in the Braille dot pattern. A stylus is used to press the paper against the pits to form the raised dots. A person using Braille writes from right to left; when the sheet is turned over, the dots face upward and are read from left to right.

The Braille Characters

Machine-Produced Braille

Braille is also produced by special machines with six keys, one for each dot in the Braille cell. The first Braille writing machine was invented in 1892. A recent innovation for producing Braille is electric embossing machines similar to electric typewriters.

Multiple copies of Braille materials are made with embossed zinc plates that are used for press masters. These plates are produced by a stereograph machine invented in 1893. In the 1920's the interpoint system was developed to emboss both sides of a sheet of paper without the dots on-one side opposing those on the other side. Recently, a computer programme for automatically translating printed English into contracted Braille has been used to produce stereograph plates and to provide Braille feedback from a standard teletypewriter keyboard.

How Helen Keller Wrote Her Story

The way in which Miss Keller wrote her story shows, as nothing else can show, the difficulties she had to overcome. When we write, we can go back over our work, shuffle the pages, interline, rearrange, see how the paragraphs look in proof, and so construct the whole work before the eye, as an architect constructs his plans. When Miss Keller puts her work in typewritten form, she cannot refer to it again unless some one reads it to her by means of the manual alphabet.

This difficulty is in part obviated by the use of her braille machine, which makes a manuscript that she can read; but as her work must be put ultimately in typewritten form, and as a braille machine is somewhat cumbersome, she has got into the habit of writing directly on her typewriter. She depends so little on her braille manuscript, that, when she began to write her story more than a year ago and had put in braille a hundred pages of material and notes, she made the mistake of destroying these notes before she had finished her manuscript. Thus she composed much of her story on the typewriter, and in constructing it as a whole depended on her memory to guide her in putting together the detached episodes, which Miss Sullivan read over to her.

Last July, when she had finished under great pressure of work her final chapter, she set to work to rewrite the whole story. Her good friend, Mr. William Wade, had a complete braille copy made for her from the magazine proofs. Then for the first time she had her whole manuscript under her finger at once. She saw imperfections in the arrangement of paragraphs and the repetition of phrases. She saw, too, that her story properly fell into short chapters and redivided it.

Partly from temperament, partly from the conditions of her work, she has written rather a series of brilliant passages than a unified narrative; in point of fact, several paragraphs of her story are short themes written in her English courses, and the small unit sometimes shows its original limits.

In rewriting the story, Miss Keller made corrections on separate pages on her braille machine, Long corrections she wrote out on her typewriter, with catchwords to indicate where they belonged. Then she read from her braille copy the entire story, making corrections as she read, which were taken down on the manuscript that went to the printer. During this revision she discussed questions of subject matter and phrasing. She sat running her finger over the braille manuscript, stopping now

and then to refer to the braille notes on which she had indicated her corrections, all the time reading aloud to verify the manuscript.

From Helen Keller, The Story of My Life (New York: Lancer, 1968), pp. 326-28.

The following is a partial list of other books written by Helen Keller:

Optimism (1903), The World I Live In (1910), My Religion (1927), Midstream (1929), Hellen Keller's Journal (1938), Let Us Have Faith (1940), Teacher: Anne Sullivan Macy (1955).

Sample of Helen KeIIer's handwriting, 1891

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet